By Yara Abi Nader

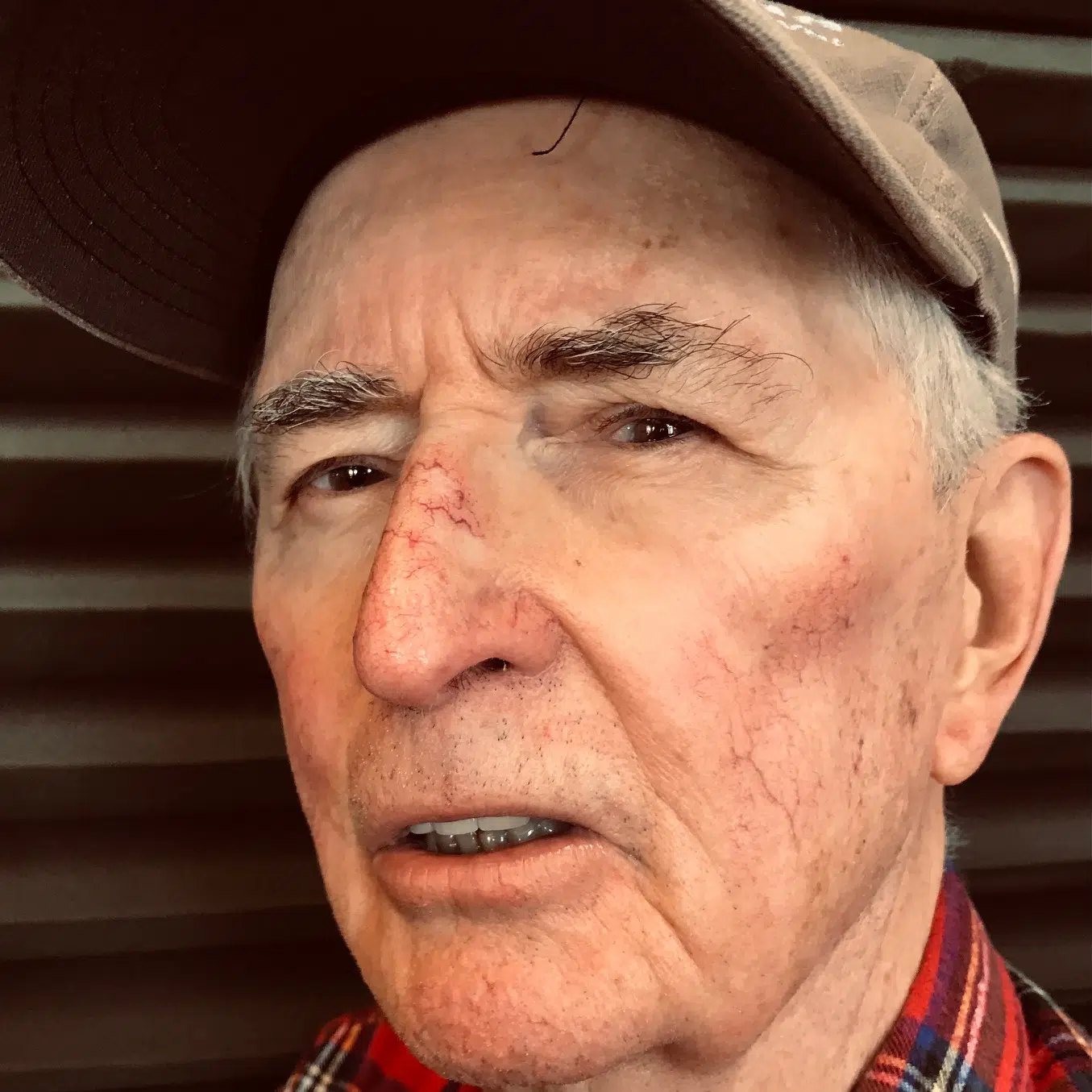

BEIRUT (Reuters) – Before he went missing on Aug. 4, Ghassan Hasrouty, an employee of Beirut’s giant grain silos for 38 years, thought he was working in the safest place in the city.

The reinforced concrete walls and underground rooms were his shelter for many days during Lebanon’s 1975-1990 civil war.

He used to tell his family that he was more worried for them than himself when he set out to work each morning.

At 1730 on Tuesday, Hasrouty called his wife, Ibtissam, saying he would be sleeping at the silos that night because a shipment of grains was arriving and he could not leave.

He told her to send him a blanket and pillow.

She has not heard from him since.

Tuesday’s explosion in the port of Beirut, the biggest ever to hit the city, destroyed the silos, killed at least 158 people and injured more than 6,000. It left an estimated 300,000 Lebanese effectively homeless as shockwaves ripped miles inland.

The health ministry on Saturday said 21 people were still missing.

Officials have said the blast was caused by 2,750 tonnes of ammonium nitrate, a substance used in manufacturing fertilizers and bombs, which had been stored for six years in a nearby warehouse without adequate safety measures.

The government has promised to hold those responsible to account, but residents are seething with anger.

Hasrouty’s family believe that he and six of his colleagues are somewhere under the silos and they are holding out hope that they are alive.

They say the rescue response has been too slow and disorganised and that whatever chance there was for finding them alive is being lost.

The family says that despite giving the authorities the exact location of where he was believed to have been at the time of the explosion, the rescue effort did not start until 40 hours later.

At their home in Beirut, the family has gathered every day, anxiously awaiting information.

“These people who are missing are not just numbers,” says Elie, 35, Hasrouty’s son.

“We need to highlight the mediocrity of management of this disaster, of this situation, how bad it is managed… not to repeat such a horrible disaster and horrible management.”

Hasrouty, whose own father worked at the same silos for 40 years, was dedicated to his job, his family says.

His daughter Tatiana, 19, flits between resignation and hope.

“We did not even get a chance to say goodbye,” she says. “But we are still waiting for them… to all come back.”

(Writing by Ayat Basma; Editing by Nick Macfie)