By Laura Gottesdiener

MATAMOROS, Mexico (Reuters) – A sprawling camp in the Mexican city of Matamoros, within sight of the Texan border, has since 2019 been one of the most powerful reminders of the human toll of former President Donald Trump’s efforts to keep migrants out of the United States.

The camp has dwindled to just a few dozen in residents in recent days, after hundreds of asylum seekers living there were finally allowed to cross the border to press their claim to stay in the United States.

President Joe Biden last month rolled back the program – known as the Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) – that had forced asylum seekers to wait in Mexico.

Biden’s wife, Jill, visited the camp during last year’s presidential campaign to witness the difficult conditions first hand.

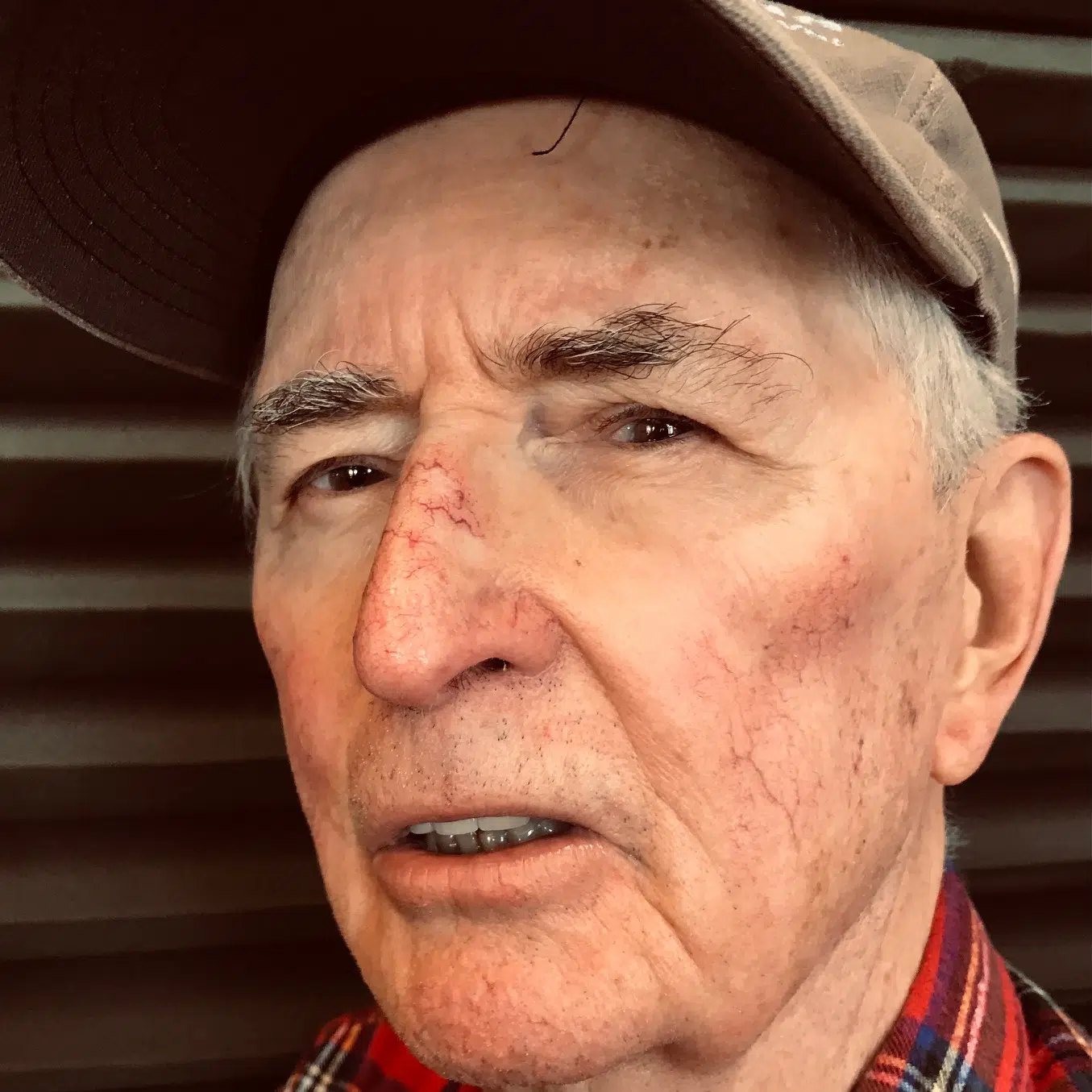

“If it hadn’t been for this camp, I don’t think they would have ever ended MPP,” said Honduran asylum seeker Oscar Borjas, one of the last remaining residents.

Like hundreds of asylum seekers expelled from the United States to this crime-ridden town, Borjas began sleeping near the foot of the international bridge across the Rio Grande out of fear and necessity.

But the migrants also intended to make a statement, he said: a visible reminder of the human toll of the MPP program. “We were there so that people would see us; see it wasn’t fair what they were doing to us.”

As of Friday, some 1,127 people in the MPP program across Mexico have been permitted to enter the United States since Biden rescinded the policy last month. More than half of those were from the Matamoros camp, according to the U.N. refugee agency.

Once home to more than 3,000 people, the camp now stands largely deserted, except for the few whose appeals to enter the United States have been denied, Borjas said.

“I don’t know what I’ll do now. I can’t go back,” said Borjas, who said he faces the threat of murder in Honduras for supporting an opposition party.

“LET’S UNITE”

The Trump administration touted the MPP program as part of its successful efforts to reduce immigration and cut down on what it called fraudulent asylum claims.

Since 2019, the policy pushed more than 65,000 migrants back into Mexico as their asylum cases wound through U.S. courts. The majority gave up waiting and left Mexico. Thousands more crowded into shelters or apartments, disappearing from sight.

But in Matamoros, which had scant resources for migrants, families opted to sleep in the plaza at the foot of the bridge.

“We said ‘Let’s unite’ and that’s how the camp in Matamoros began,” said Honduran asylum seeker Josue Cornejo, who was returned to Matamoros along with his wife and their children in August 2019.

Parents scavenged cardboard to stop the summer heat radiating off the pavement from burning their children’s skin. The men formed a guard watch.

Aid workers arrived. So did Matamoros’ criminal groups, which doled out beatings and siphoned off donations, migrants say.

As the camp population ballooned, the tents sprawled from the plaza to the wooded banks of the Rio Grande, where residents braved contamination and undercurrents to bathe and wash their clothes.

The migrants resisted federal government efforts to house them in a makeshift shelter miles from the border.

Life took root in a way migrants say they had never expected, making the lengthy wait in Mexico slightly more bearable.

They formed church groups, supply distribution tents and kitchens with handmade earthen ovens and stoves improvised from old washing machines.

Nicaraguan asylum seeker Perla Vargas and other migrants launched a tent school that provided music, dance, English and Spanish classes to dozens of children each day, including her two grandchildren.

There were quinceaneras, romances, and at least one wedding.

Consuelo Tomas, an indigenous Q’anjob’al Guatemalan asylum seeker, gave birth inside the camp and named her newborn Andrea in honor of the child’s grandmother, who died years earlier trying to cross the Sonoran desert to reach the United States.

Insecurity and hardship reigned.

The weather whiplashed between scorching heat and freezing cold. Human rights groups documented kidnappings and rape of asylum seekers in Matamoros. Occasionally, migrants’ bodies washed up along the river bank.

Some mothers, including Salvadoran asylum seeker Sandra Andrade, sent their children to cross the U.S. border alone illegally out of concern for their safety.

“It was one of the most difficult decisions I’ve had to make, but I wanted to protect them,” she said.

MATAMOROS TO WASHINGTON

At times, the camp served as the launch pad for protests: from a blockade of the international bridge that halted traffic for hours to demonstrations and all-night vigils opposing Trump’s re-election.

Aaron Reichlin-Melnick, policy counsel at the American Immigration Council, said that MPP program might have succeeded in obscuring the plight of these migrants from the American public if it were not for the Matamoros camp.

“It was the one place where you couldn’t deny that what we were doing was inflicting harm on people,” he said.

Last month, the Biden administration said it would allow about 25,000 migrants in MPP to enter the United States to pursue their cases. Matamoros camp residents were to be among the first in line, it added.

Buoyed by the news, migrants had prepared for their departure in late February: snapping farewell photographs and snipping haircuts for fellow migrants. The sound of bachata music rang out as children hopped about, rehearsing for their final dance recital. Andrade packed up her remaining protest signs and distributed donated pairs of tiny sneakers.

“It’s so the kids can cross into the United States in brand new shoes,” she said.

(Reporting by Laura Gottesdiener in Matamoros, Mexico; Editing by Daniel Flynn and Alistair Bell)